The People of Herring Road

When we invited Ms. Juanita Winfield to participate in our Humans of Legal Aid project, it wasn’t long before we had a whole crew of subjects to interview: the people of Herring Road. On the phone that first day, Ms. Winfield gave me the number of her uncle, Mr. Henry Morgan, age 87. She told me that he was very eager to tell his story, and that he knew more than any of them because he had been around the longest. She suggested that we visit him at his retirement community in North Decatur, and told me that she would round up the others and they would carpool over to see him. We didn’t know how many people Juanita had gathered, but we were excited to get the chance to interview people who had such long ties with Atlanta — “Grady babies”, as many of them proudly proclaimed.

On the day of the interview, we met Mr. Morgan in the community room of his apartment building, and waited for the others to arrive. Arriving in twos and threes, eventually seven people settled into the chairs we had set out for the interview, all of them relatives except one — Ms. Gussie McCoy Character — who “might as well have been”. And all of them had once lived on Herring Road in Cascade Heights, a neighborhood in southwest Atlanta. Today, only Ms. Juanita Winfield remains on Herring Road, in the home where she grew up. But she tells us with a somber head shake that the neighborhood is not what it once was. When she was coming up, all of the neighbors were like family (if they weren’t already family by blood). The boundaries of the properties were fluid, and children ran from yard to yard. Now, Juanita tells us, the neighbors have put up fences, and although she and her next door neighbor have introduced themselves, they don’t really know each other.

A quick Wikipedia search shows a history of Cascade Heights that jumps from the Civil War era all the way to the 1960s. Wikipedia says: “In the early 1960s the area was a predominantly white neighborhood.” But the residents of Herring Road remember Cascade Heights differently. They know that the story being told about Cascade Heights is not the full story.

Mr. Henry Morgan especially wants to paint a clear picture of the neighborhood. Before our interview, he sketches out a map of the town’s streets, before crumpling the paper up and deciding to explain it orally. He meticulously explains the way the streets were laid out and how the houses looked and where the creeks were. He explains where the church is, and recalls that before there was a church, there was a school, and before there was a school, there was a baseball diamond. Each person’s memories of the place are crystal clear, and it is easy to imagine. As one family member talks, the others nod and smile in remembrance. But despite all of that, the place holds a lot of pain. Mr. Morgan says that he can no longer drive through that area; it makes him want to cry. The place has changed so much to be almost unrecognizable. Still, they remember.

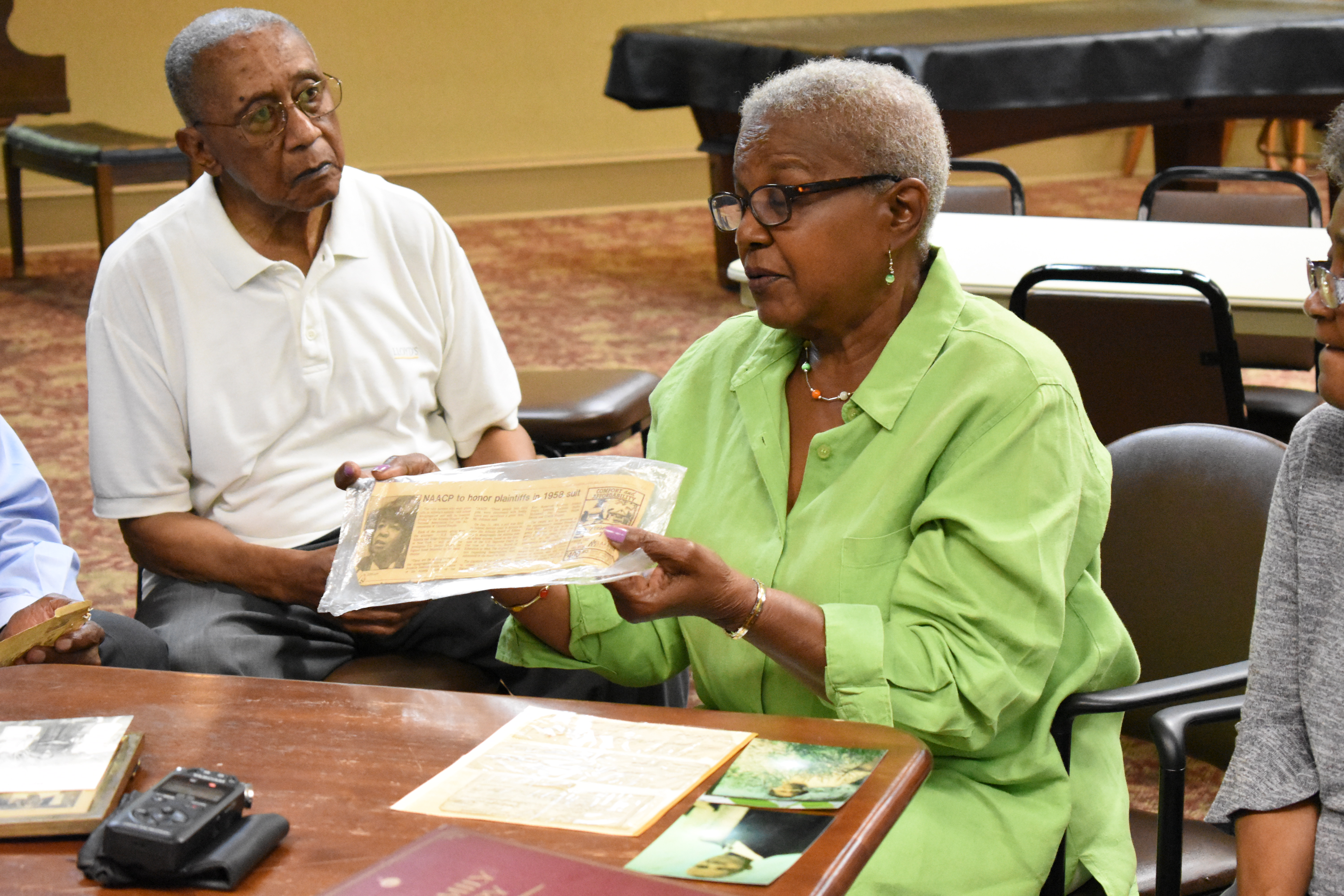

Marcia Jackson Walker 72, brings along a family memory book, stuffed full of old clippings and family photographs. She spreads them out on the table, and the family gathers around, shuffling through the papers, letting them stir their memories.

Phyllis reaches forward and picks up a newspaper article. “This one is from the Atlanta Journal Constitution. This is dated 1964,” she says. “They were honoring the plaintiffs in the 1958 suit. That’s where you had 9 parents who were plaintiffs in the historic Atlanta 1958 school desegregation suit, getting them to comply with the Brown decision, and as I mentioned, two of those plaintiffs were residents on Herring Road. My father, Leonard Jackson, and her father, Charlie Piers.”

My colleague, Stephanie, asks, “Were your fathers politicians?”

Phyllis quickly responds, “No, they were not politicians. They were fathers who wanted a good education for their children, and other children in that neighborhood. And you could definitely say they were community activists. You could say they were activists period. Because what they were doing was going to impact all of the children in the city, not just those of us in Cascade Heights. And back then, trust me, my sister and I could tell you, it took a toll. It was really risk-taking, because that’s when whites would ride by at night and shoot into the houses.”

“Or during the day,” Caecilia Jackson interjects.

“Yeah, or during the day also,” Phyllis agrees.

The laughter fades away and they soberly look down. The mention of violence brings up a memory for Caecilia. She looks around the table as she starts her story.

“My sisters and I would be out on the porch playing, the front porch, and I’ll never forget the incident that happened. We were out there playing and two white guys came in a car, and we didn’t know what they were doing, because they were on the street but across from our house. So when they left, we went to find out what had happened. And we saw the old polaroids you used to have. We actually saw the picture they had taken of our house. And later, they came by ….

Phyllis picks up the story, “And in the evenings, neighbors would sometimes gather, like my mother and Juanita’s mother. They were sitting on our front porch — on an old style glider, and some of us were in the yard playing ring around the mulberry bush. This image is so vivid, I shall never forget it. Because we were playing ring around the mulberry bush and I remember glancing up at my mother and seeing her slowly rise from her seat and looked like — she just had a look of horror on her face. And I looked from where her face was to the street and saw these guys approaching in this red truck, and I could see the barrel of a gun. And I just have to credit it all to God because as they approached, they were going so fast that when they shot, it blew out the attic window and it didn’t strike any of us. But I will never forget that look on my mom’s face, as long as I live, because she was horrified. But… that’s the kind of thing that we lived through.”

This memory, many decades past, still leaves Phyllis shaken. And yet, there’s a kind of resignation in her voice as she finishes the story. The seven of them have lived through so much change, much of it violent. Their perseverance seems at least in part due to the strength of their community. When houses were burned down in acts of hate, the community re-built them. If neighbors got into a heated argument, other neighbors would come out and quickly diffuse the situation. When white men came into the community in an attempt to get the residents of Herring Street to sell their homes, they stood resolutely together and refused to leave.

Cascade Heights still exists, but not the way it once did. It has morphed and changed much throughout the past 8 decades. It feels, to the old residents of Herring Road, more divided and less like a community. But the spirit of the place lives in their memories.

They remember when their fathers fought for desegregation. They remember being bussed to schools many miles from home when the school district ignored the law in the Brown vs. Board of Education case. And they remember when they were finally allowed into schools with the white children — in some cases, when they were the first black children to desegregate those schools. They remember the ridicule, and the hate crimes, and the fear. But they also remember the strength and solidarity of their community. They remember their neighbors banding together to care for each other — to make their class a home cooked meal for lunch every day when they had no cafeteria; to sue the city when their rights were being ignored; to share a laugh on a front porch after a long day of work. Their memories are intertwined with the beauty and the pain of that time and place. There seems to be no separating the two.

And yet, I think, hope prevails. Gussie expresses her hope for the younger generations, “When I think about my life then and now, I first of all look at the success I feel I’ve made. But I think that we should not forget from whence we came. And [we should] share all of the experiences, be they good or bad, with our younger generation, and have an open mind toward what’s going on now and try to influence them to take what they have now and do what we did with what we had then… Letting them know that if they try, they can.”

Phyllis adds, “Never forget your history. And even learn to embrace and enhance part of it and teach it to those who don’t know. We have come from being referred to as slaves, the n word, and colored, then negroes, to blacks, and now African Americans. You know, when you are given the chance to shape your own identity, embrace it. Enhance it. But don’t forget that you are standing on the shoulders of some of those who had to suffer consequences to get you to that point.”

The people of the old Cascade Heights may have moved away, but the spirit of the place clearly lives on inside of them.

Through our Humans of Legal Aid project, we want to offer you a glimpse into the lives of the people affected by our work — our clients, our staff, and our volunteers. We interviewed each of these people with the desire to hear a deeper, fuller story of their lives. To read more excerpts from the interviews, visit: atlantalegalaid.org/humans-of-legal-aid/